When most people consider hearing loss, they imagine someone cranking up the volume on the television or frequently asking "What?" However, having worked as an audiologist for over two decades, I've discovered that hearing loss often extends beyond mere auditory issues.

It's also related to identity, emotions, and effort. For numerous individuals, that’s the harder part .

As both a healthcare provider and university instructor, I've had the experience of working with many individuals who were reluctant to get assistance — not due to financial constraints or lack of availability of services, but because it involved acknowledging something they weren't prepared to embrace that an essential shift had occurred.

They were afraid of What that alteration revealed about them? . Regarding aging. Regarding control. Regarding becoming "that individual" with hearing aids.

I've come to realize that dealing with hearing loss is as much an exploration of the mind as a physical ordeal . And maybe if more people understood that, they’d feel less alone and more willing to take the first step.

When hearing deteriorates, the brain needs to exert more effort.

Hearing loss isn’t like flipping a switch between "typical" and "completely deaf." Instead, it sneaks up gradually over time. At first, you find yourself frequently asking others to speak again. Social gatherings leave you feeling drained. You chuckle at jokes even though you missed the punchline. Gradually, you begin to drift away from the fringes of discussions until finally, you avoid them altogether.

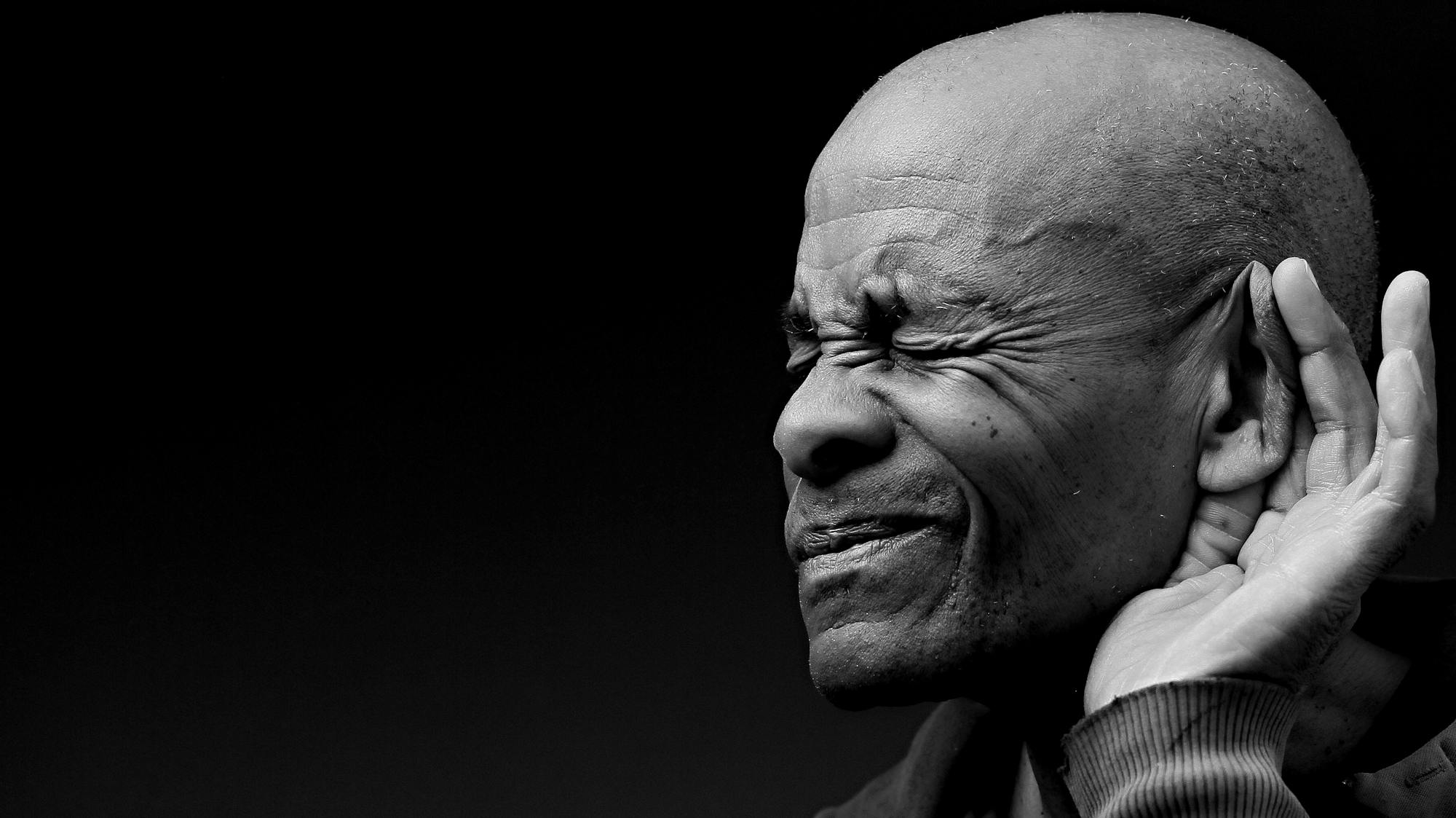

Many individuals aren't aware that hearing impairment burdens the mind. Think about attempting to read a book in a poorly lit space; you manage to do so, yet it demands greater focus. Similarly, listening proves challenging for those experiencing hearing difficulties, particularly amidst loud surroundings. In these situations, their brains exert extra effort to compensate for missing auditory details.

Over time, this Ongoing tension results in mental exhaustion. And diminished mental capability when it comes to tasks such as remembering and making decisions.

It’s not merely an assumption; neuroimaging and long-term studies demonstrate this clearly. extensive studies such as the ACHIEVE trial A randomized controlled study conducted by Johns Hopkins researchers revealed that addressing hearing loss in elderly individuals susceptible to cognitive decline decreased overall cognitive impairment by almost half within a span of three years.

The impact was most pronounced amongst those who had an elevated risk because of reduced cognitive reserves and greater social susceptibility.

This isn't due to hearing loss causing dementia directly. Instead, the ongoing mental effort required along with the typical isolation from society that comes with hearing loss sets up circumstances conducive to dementia. Over time, the brain becomes less stimulated, less resilient, and more susceptible. .

Psychology has a more significant impact than many individuals recognize.

If hearing loss impacts the brain and overall wellbeing, then why aren't more individuals seeking assistance? That’s when psychology steps into the picture.

People make decisions based primarily on their emotions. Although we believe ourselves to be logical, we actually depend significantly on our feelings, presumptions, and quick cognitive shortcuts. Actually, behavioral studies have demonstrated that even healthcare professionals who are well-trained still do this. make erratic decisions when influenced by emotions or personal convictions .

In my practice, one powerful force I encounter frequently is cognitive dissonance. This occurs when people experience discomfort because their beliefs do not align with their behaviors. Take for instance an individual who holds themselves as self-reliant and competent; however, requiring hearing aids may cause them to view themselves as reliant on others or somehow diminished in capability. Internal conflicts may result in denial, resistance, and even anger. .

Another common obstacle is self-efficacy — our confidence in our capability to handle tasks. I've encountered individuals who excel in their careers or hold leadership positions yet feel utterly daunted by the prospect of handling hearing aids. Their anxiety doesn't stem from the devices themselves; rather, it comes from the unease associated with tackling something new and unknown.

The perception of memory and aging can often be skewed. Forgetting a word in your 40s might prompt light-hearted jokes about having too much going on. However, experiencing this same lapse in your 60s or 70s could lead to anxiety over cognitive deterioration. Including hearing impairment into the equation intensifies these worries even more.

This is precisely why the narratives we create for ourselves—and those imposed upon us by society—hold significant importance.

Being truly heard

Your initial audiology visit goes beyond a simple hearing assessment; it's an important discussion. During this session, we delve into how hearing loss impacts various aspects of your life such as personal relationships, professional duties, and self-assurance. Together, we'll address your aspirations, worries, and priorities.

Occasionally, individuals anticipate departing with both a hearing aid and a cure. Managing hearing loss is a procedure. , rather than a simple transaction. Adjusting requires time as your brain needs to reacquaint itself with sounds it hasn't perceived clearly in ages. This process might feel disorienting initially, yet simultaneously, it’s incredibly liberating.

That’s precisely why the bond between clinician and client holds such significance. Studies repeatedly demonstrate this importance. the key element for effective counseling — be it for listening or any other aspect — hinges on trust. When individuals sense safety, worthiness, and comprehension from others, they become more inclined to attempt new things, evolve, and expand their horizons.

Not weakness, but wisdom.

I frequently remark that hearing aids resemble umbrellas; they do not eliminate the rain, but they keep you from getting wet. Likewise, hearing aids cannot reverse hearing loss or halt the progression of aging. However, they can lessen the effort required for listening. They enable you to remain socially engaged and enhance your overall quality of life.

And as the ACHIEVE study Highlights that the cognitive advantages of interventions are concrete, particularly for individuals more susceptible to cognitive deterioration. By aiding people in hearing improvement, we're not only enhancing their social interactions; we're also decreasing their likelihood of experiencing rapid mental decline.

Even if hearing aids did not provide cognitive benefits, they would still be worthwhile: for the pleasure of engaging in conversations, being able to be present, and having the opportunity to fully take part in life.

I understand that asking for assistance can be challenging. However, seeking support doesn't imply you're damaged; rather, it indicates your appreciation of relationships. It signifies your desire to remain engaged. Most importantly, it shows you're taking charge.

Here’s what I want everyone to remember: If you find it hard to hear, go for a hearing test — even as a starting point to know where you stand.

If you're presented with treatment options, allow yourself some time to adapt. The focus should be on advancement rather than flawlessness.

If you notice someone distancing themselves socially, reach out to them. Hearing loss may be unseen, yet its impacts are evident.

And if you're already using hearing aids, congratulations—you're taking a remarkably positive step for your cognitive health, your interpersonal connections, and your long-term well-being.

As audiologists, our role extends beyond repairing ears; we assist individuals in reestablishing connections with their surroundings. That's truly noteworthy.

Bill Hodgetts has secured financial support from several governmental bodies and foundations for his research projects, such as Mitacs, the Western Economic Partnership Agreement, the Oticon Foundation, among others.